The Making Of A Master Bike Builder | DRAWING THE LINE

In some parts of the world, apprenticeship is a recognized route to technical competence.

By James Parker Photos: Charles Mann & Garrett P. Vreeland

Posted September 29, 2015

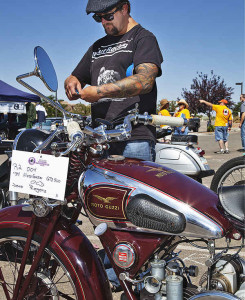

The Motorado Motorcycle Club of Santa Fe held it’s first Antique Motorcycle Show on Sunday July 17 in 2012 and it was a rousing success which attracted over 100 antique motorcycles and hundreds of spectators. Marc of OCD Custom Cycles in Santa Fe maintains this 1934 MotoGuzi for Dean Rogers.

Back in 2012, I was asked to be a judge at an annual motorcycle show in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where I’ve lived for many years. I was happy to lend my expertise, such as it is, but careful to make clear my knowledge of antique bikes is quite basic. I’m not well versed in the minutiae of motorcycles of the past; most of my work with motorcycles has focused on what might appear in the future.

This was certainly not a Pebble Beach-caliber show, but I was pleased to see many interesting and worthy motorcycles on display. By the end of the day all the judges agreed on which bike was best in show: a 1934 Moto Guzzi GTS 500, a beautiful machine in iconic Italian red and chrome that abounds with innovative technology.

I was introduced at the show to Marc Beyer, who expertly restored the Guzzi, but I didn’t really get to know him until recently. Beyer, a German transplant in the US since 1998, owns a shop in Santa Fe called OCD Custom Cycles. There, with the able help of his partner, Frances Sayre, he restores classics like the Moto Guzzi, constructs interesting custom bikes, and performs more prosaic maintenance and repair of almost any motorcycle.

Talking with Beyer, two words stood out: “apprentice” and “master.” Here in the US we hardly recognize the word “apprentice,” but in other parts of the world, apprenticeship is a recognized route to technical competence. Superficially similar to what we might call “on-the-job” training, apprenticeship is something more formal, with regular testing and evaluation of both technical/mathematical learning and actual hands-on skills.

Beyer’s apprenticeship story began after high school, when he was accepted into a program run by automaker Mercedes-Benz. This was the late 1980s, and Mercedes needed experienced craftsmen as the company expanded their dealership network into what had been the former East Germany. Beyer moved to Dresden, where he specialized in metalwork, learning a range of skills from welding to forming to machining and more.

After the apprenticeship ended, he continued his education and gained a Meisterbrief (master’s degree) in automotive engineering then immigrated to the US to take a position with Europa International, a company that imported the four-wheel-drive Mercedes Gelandewagens and modified these to meet US standards. After Mercedes took over that company in 2004, it was on to a BMW motorcycle dealer as shop foreman. But Beyer had always wanted his own place, so in 2011 he started OCD Custom Cycles.

In the US today, we have an education system that has, as one of its primary features, high cost. That cost has become a dramatic debt burden for an entire generation of students. The apprenticeship, on the other hand, is a formal system in which training and education happens while the student does productive work and gets paid for that. The pay is not initially lucrative, of course, but the student usually doesn’t end up with such considerable educational debt. I’ve known people who have gone through apprenticeship programs in the UK, and now hearing of Beyer’s experience in Germany, I ask myself if apprenticeship isn’t the best way to gain technical proficiency. But apprenticeship, at least in its initial stages, is a cost to employers. In times of increasing austerity, is this just another cost that companies would like to eliminate?

Marc Beyer certainly appreciates his experience, and although he currently can’t justify taking on an apprentice, he is involved with a local school offering a mentorship program that provides selected youngsters with a motorcycle, a workbench, tools, and instruction to help them build a custom bike. It’s a long way to become a master, but you have to start somewhere.